Making Sense Through Sensation In Qualitative Research

Sometimes it seems like nothing makes sense anymore.

We have more data than ever before, which we can analyze with automated tools in the blink of an eye. So, why is it that things don’t make sense?

We take action to accomplish tasks, generating words, generating sounds, generating pictures, generating code, but what is it all for? We make more, but with less of an idea of what we’re making it for.

When I get this feeling of senselessness, I bake cookies.

Cookies make sense.

Cookies make sense because they provoke our senses.

I’m not just talking about the way cookies feel in our mouths, though of course that’s fantastic. I’m also thinking of the pleasure with which the scent of a little bit too much vanilla extract hits my nose as it spills out of the bottle cap I use to go through the pretense of measuring it. I’m talking about the strain that my wrist feels through the wooden spoon as the dough reaches its proper thickness, prompting me to pull back and do the final mixing slowly, so the wood doesn’t snap. I’m forced to practice restraint.

I could buy cookies from the grocery store. That would be a more convenient and efficient choice. I take the time to make cookies instead, because I want more than just to eat cookies. I want the entire sensory experience of making cookies, because it makes me feel grounded. The process of making cookies helps me regain the feeling that things make sense.

It's remarkable how the word sense refers to both a well-balanced mindset and the means through which our bodies bring information about the outside world into our minds. I have a feeling that these two aspects of the word sense are not as distinct as they first seem. When I do things like baking cookies, or washing the dishes, or gardening, or taking a walk, I get the sense that engaging the world through actions that require attention our physical senses is a reliable way to reach a sensible frame of mind.

Sense isn't just data collection and processing. Sense isn't just the wisdom that come from clear thinking. Sense is something that occurs at a place in our subjective consciousness where our internal thoughts and experiences meet information from the outside world to create something on a higher order of complexity, a feeling that gives us coherent motivation and direction.

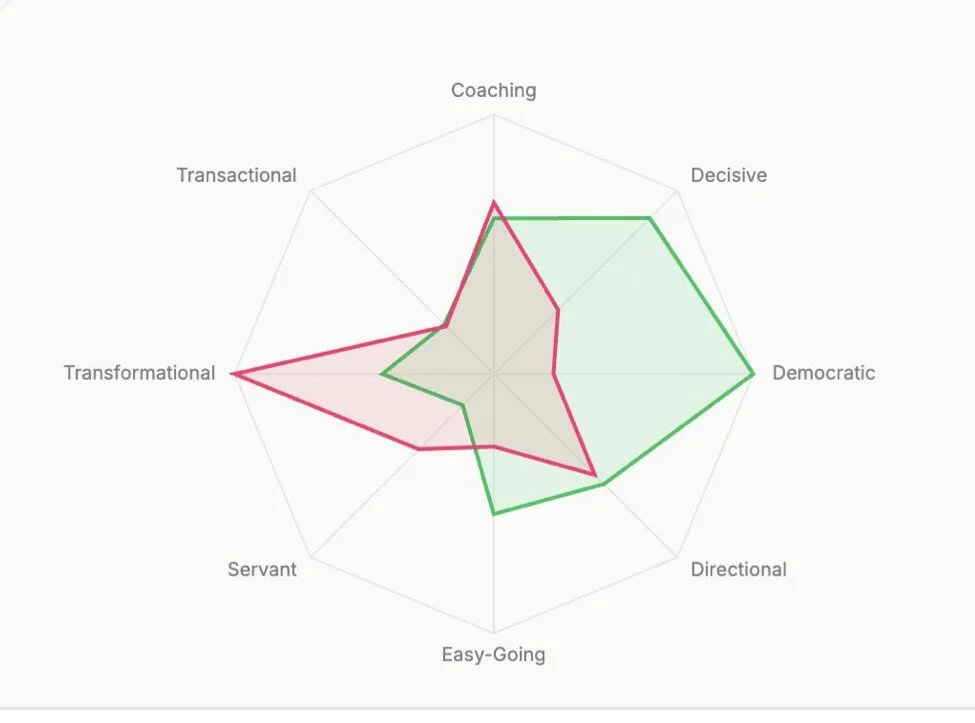

This evening on LinkedIn, I ran across a post promoting a piece of software that automatically tracks the language that people use in their organization's internal communication. The creator of the software suggested that it could be used as a tool for "understanding your company culture” by generating diagrams such as this:

Is this what culture looks like?

I don't argue that it might be useful for corporate executives to track data about patterns in the language employees use in their work. Whatever utility it may have, however, this diagram is not what culture looks like, any more than a list of ingredients on a package of cookies is what a cookie looks like. Culture is the way that people live, and the way that they think and feel about how they live. It's not just the words that they use, much less a chart that represents a statistical analysis of the words they use.

It's easy these days to get lost in the abstractions of information, or to connect to our work remotely through language over a digital distance, or to outsource our thinking entirely to automated mimics of humanity. There's a lovely kind of structure to that kind of work, but it's removed, at a distance, and its connection to an enduring sense of purpose easily wavers. We can get so immersed in the cognitive tasks of our work that we forget why our work matters.

When I feel that way, I close down my computer, get up out of my chair, and do something like baking cookies. I'm not the only one.

Samin Nosrat, a chef known for the book Salt Acid Fat Heat, has written about the cultural power of acts of cooking in a gorgeous new title called Good Things: Recipes and Rituals to Share with People You Love. As I explored its pages, I was struck by the way that her writing about food is infused with ideas about the human experience. Nosrat offers much more than just an instruction manual for creating delicious food. The book is also a reflection on how to live. She writes:

"A good life is one where time - and its fast companion, attention - are the most precious gifts I can give or receive. The beauty of cooking is that it's a vessel for both time and attention. Cooking for someone, or sitting down for a meal together, is about more than nourishment - it's a way to share what's most valuable to you with the people you care about."

Nosrat's wisdom is grounded in the development of a way of working that cultivates something beyond the mere accomplishment of tasks. She focuses on the process of her work in addition to its outcomes. When she cooks, she isn't just making food. She is also crafting experiences, both for the people who eat her food and for herself in the experience of cooking.

"Good cooking isn't about mindless repetition. It's about being completely present with an experience as it unfolds. I believe it's the job a good recipe to guide and empower a cook to use all of her senses - including common sense - to make the best choices in moment."

Reading these words, it occurred to me that what Nosrat says about cooking has something in common with the way that I think about my own work: Qualitative market research. A good qualitative market research project is one where time, and attention, are the most precious gifts I can give or receive. The beauty of qualitative market research is that it's a vessel for both time and attention. Qualitative market research is a way to share what's most valuable to the people your clients care about.

Good qualitative market research isn't about mindless repetition of an algorithmic set of questions. It's about being completely present in the experience of being with a client's customer as the research process unfolds. I believe that it's the job of good qualitative research design to guide and empower researchers to use all of their senses, including common sense, to make the best choices of specific lines of questioning in the moment.

What good qualitative research shares in common with good cooking is a grounding in a rich sensory experience. The research methodology I most often use centers around an interviewing process called visualization, in which people re-engage with evocative moments from their past by calling to mind visual, auditory, and other sensory stimulus surrounding the experiences. This approach moves people beyond abstract assessments and opinions by recontextualizing them in the physical world. As with almost all qualitative research, it's best done in person, face to face with another human being.

Engaging with the full sensory experience of physical context of consumer behavior enables researchers to get to the elegant balancing point of sense. That's why qualitative researchers often describe their work as sensemaking.

It's my professional equivalent of baking cookies. When the abstractions of business and the marketplace start to lose their relevance, that's when I know I need to close down my computer, grab a pen and pad of paper, and meet up with a consumer, a person who lives the business that marketers think about. That kind of knee-deep immersion in the research process is something I encourage my clients to participate in as well.

Anything less than that is half-baked.

Come bake with me.